Why Engineering Reality Defeats Political Theatre in AI

You’re reading headlines about US companies adopting Chinese AI models despite the tech rivalry between America and China. The framing treats this as surprising, maybe even controversial.

But here’s what those headlines miss. This isn’t about geopolitics. It’s about engineering reality overriding political narrative when the balance sheet gets involved.

I’ve watched organisations make AI implementation decisions for years now. When you actually sit in those rooms, the conversation doesn’t sound like the media coverage at all.

The Model Doesn’t Matter

People fixate on the wrong problem when they think about AI implementation. They believe they need to engineer a model, train something custom with their data, build something from scratch.

That understanding comes from the days of machine learning when you actually had to train your own models. But that’s not how this works anymore.

What matters is the engineering around the model. The data engineering. How you structure the data going in, what happens to the output, how you fine-tune the prompts, whether you’ve written proper evaluations.

The model itself? You can switch that out. Put another one in. The infrastructure you build around it is what delivers the measurable outcome.

Where the Real Cost Lives

When organisations choose between a closed model from OpenAI and an open-source Chinese model like Qwen, the engineering difference produces massive financial gaps.

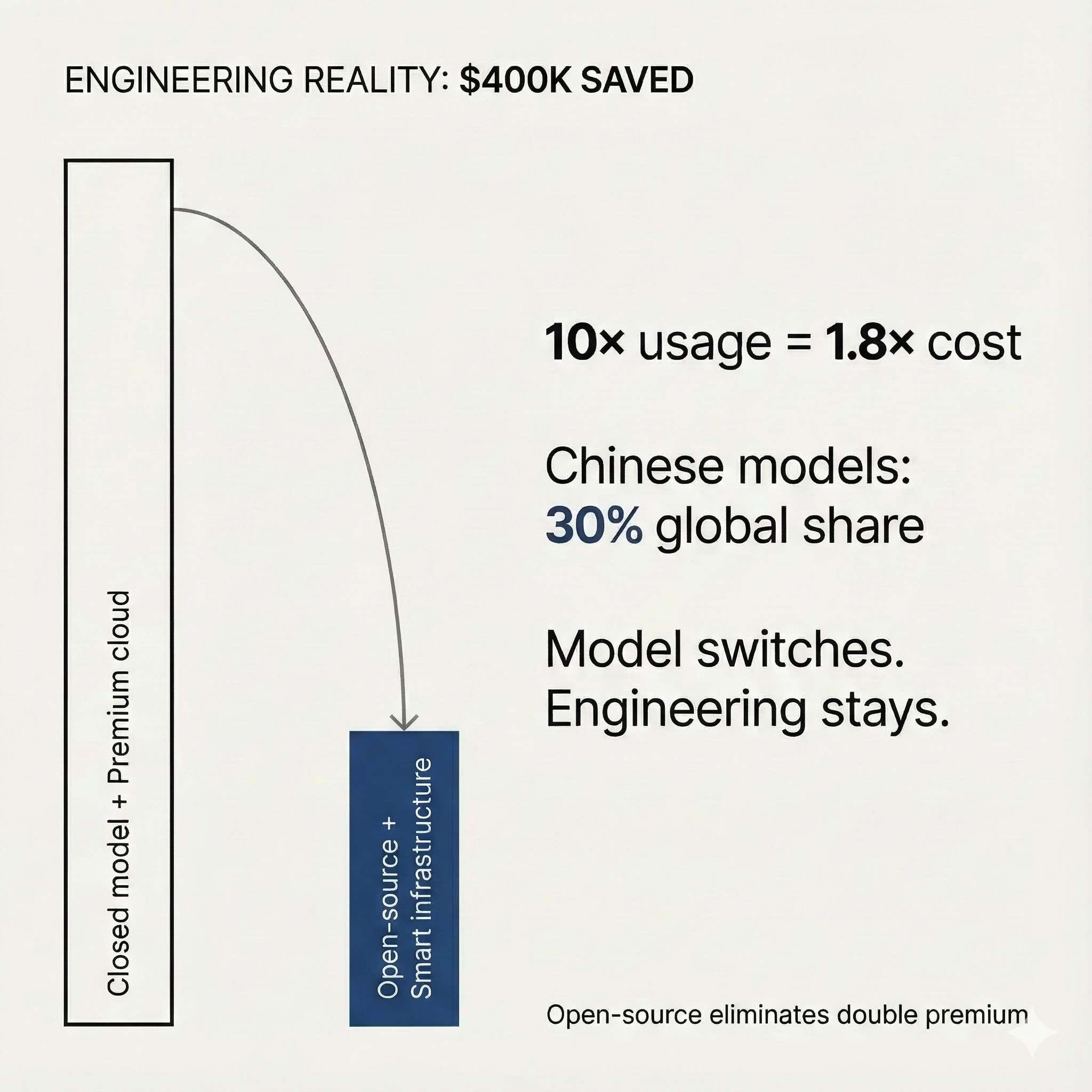

One business saves $400,000 annually by switching to Alibaba’s Qwen models. That’s not a rounding error. That’s balance sheet reality.

The cost structure breaks down like this. When you host on Azure, AWS, or GCP without a long-term contract, they charge premium rates. Add a closed-source model on top of that infrastructure, and you’re paying premium on premium.

Open-source models eliminate both layers. You take the model from Hugging Face or GitHub, deploy it to your own infrastructure or a smaller cloud like Hetzner or DigitalOcean. These smaller players offer pure virtual machines at a fraction of what the big clouds charge.

The cost of inference drops dramatically because you’re not paying the closed-model premium and you’re not paying the enterprise cloud premium.

This is the work we do at ML Sense. We help businesses implement AI with the architectural oversight and domain expertise that keeps systems secure, compliant, and actually working. But here’s the critical part: we only take on clients when we know we can make them 10x more than what we charge.

That threshold matters because it forces us to focus on engineering reality rather than billable hours. When your reputation depends on measurable financial outcomes, you can’t hide behind political narratives or vendor relationships. You have to choose the infrastructure and models that actually deliver.

When usage goes up 10x, your costs only increase 1.8x. Try getting that ratio from a closed model on premium infrastructure.

Why Organisations Still Choose Expensive Options

Most organisations still pick premium clouds and closed models despite the engineering reality saying otherwise. The barrier isn’t technical, it’s structural.

In tech, decisions get made by a few high-level people who have particular agendas or connections. It’s rarely about which technology performs better. It’s political.

The other factor is operational simplicity. When you use a closed-source model, you don’t have to worry about AI ops or DevOps for AI. It’s definitely easier to start with a closed model for experimentation.

But as soon as you’re spending $5,000 monthly, you need to shift to open-source. The cost differential becomes impossible to ignore when the CFO looks at the numbers.

Getting Past the Political Layer

The best way to cut through organisational politics is to speak directly to finance. The CFO cares about how well the company’s finances are managed because their bonus, career, and job security depend on it.

When you show them three scenarios—worst case, typical case, best case—they focus on the worst case. They calculate from the maximum potential loss.

You tell them that when model usage increases 10x, costs only go up 1.8x. That ratio is music to their ears. They understand immediately that scale doesn’t destroy profitability.

What Chinese Companies Understand About Constraints

The origin of the model does come up in these conversations. Chinese companies have been producing more efficient models for at least two years now. These models perform at the same level as Silicon Valley ones but cost less and remain open-source.

They’re not distilled versions or simplified models for basic tasks. They’re the most fundamental and powerful models available. Qwen ranks at the very top of Hugging Face’s comparison of major open-source models, surpassing Meta’s Llama 3.

The efficiency advantage is structural, not just pricing strategy. Chinese companies got cut off from the latest NVIDIA H100 and H200 GPUs. They only had access to 10-year-old technology for a long time.

That constraint forced them to think hard about training performance, which algorithms enhance inference speed, how to optimise the entire model architecture.

Silicon Valley companies throw electricity at problems, throw billions at compute, assume more resources solve everything. They’ve had too much money and too much compute for too long.

For the past 15 years, Western engineering culture stopped optimising code. The attitude became “the cloud will handle it.” But the cloud is full of inefficient code that’s costing companies massive amounts and draining the world economy.

The Historical Pattern of Constraint Breeding Innovation

This pattern repeats throughout technology history. The constrained player develops superior engineering practices because they have to.

When NASA engineers faced oxygen and power shortages during Apollo 13, they created an air filter using only materials on board. The constraint didn’t cripple them, it sparked exceptional problem-solving.

Research across 145 empirical studies shows that individuals, teams, and organisations benefit from constraints. It’s only when constraints become overwhelming that they stifle creativity.

Limitation breeds innovation when unlimited resources often breed waste.

Chinese AI labs trained state-of-the-art models on lower quality, non-export controlled chips by advancing their machine learning training tools. DeepSeek trained its base model with about $5.6 million in computing power whilst US rivals spent over $100 million for similar results.

01.ai trained a high-performing model with just $3 million. Their inference costs run at 10 cents per million tokens, about 1/30th of what comparable models charge.

Where Competitive Advantage Actually Lives

Technical sophistication reveals something important about decision-making. When Nvidia, Perplexity, and Stanford adopt these models, they’re prioritising capability over origin story.

The vast majority of applications don’t need absolute cutting-edge capabilities. If you need them, you go to OpenAI, Anthropic, or Google. But most use cases don’t require that level of performance.

Real competitive advantage doesn’t come from the model origin. It comes from integration depth and outcome ownership.

The engineering around the model determines whether you get measurable financial outcomes. The data engineering, the prompt structure, the evaluation framework, the infrastructure choices.

Chinese open-source models’ global share surged from 1.2% in late 2024 to nearly 30% within months. That’s a 25x increase in under a year, one of the fastest adoption curves in tech history.

This isn’t happening because of marketing or political pressure. It’s happening because organisations optimise for balance sheet reality when they have decision authority and outcome accountability.

When I work with organisations on AI implementation, I see this play out repeatedly. The companies that move fastest aren’t the ones with the biggest budgets or the most impressive vendor relationships. They’re the ones willing to measure outcomes honestly and choose infrastructure based on engineering merit rather than political comfort.

The 10x ROI threshold we maintain at ML Sense exists precisely because it cuts through this noise. You can’t deliver that kind of return by optimising for engagement duration or dependency creation. You deliver it by building the right engineering around the right models, regardless of where those models come from.

What This Pattern Reveals

The gap between political narrative and engineering reality exposes something fundamental about how technology actually advances.

Technology adoption follows engineering merit and economic incentive, not political boundaries. Open-source creates a structural force that makes origin irrelevant when outcome measurement matters.

Closed model providers built their strategy on dependency creation. They optimise for prolonged engagement, for maximising the duration you stay locked into their ecosystem.

Open-source models flip that entirely. They enable capability multiplication instead. You control your data, you own your infrastructure, you determine your cost structure.

The Linux Foundation research shows enterprises could collectively save $24.8 billion by switching to open AI models that match or exceed closed model performance. Yet 80% still choose expensive closed options despite superior alternatives becoming available within weeks.

That gap represents the difference between technical possibility and organisational reality. Between what engineering fundamentals allow and what political structures permit.

When compute becomes tight and expensive, when CFOs demand measurable outcomes, when technical sophistication allows people to see past the narrative, engineering reality wins.

The question isn’t whether US companies should adopt Chinese models. The question is whether you’re optimising for narrative alignment or balance sheet results.